BOGOTA

We got to spend eighteen months in our new house in California, now with little Eric plus Richard, age 4 and Carol, age 5 ½, and Laura a big first grader at Ellwood School in Goleta. Meanwhile, in between classes at UCSB, Robert hatched a plan to go abroad once more, this time to Colombia. He walked in one day announcing that UCSB needed a director for its Education Abroad program in Bogota. The job was essentially one of chaperoning sixteen students, not exactly Robert's forte (in his opinion, universities were wonderful places except for the students), but the chance to travel was too seductive.

I had my own motives. I looked to Colombia as a chance to visit my family—at least Brazil was part of the same land mass, even if 3,000 miles away. Eight years had passed since I had last seen my folks, and I missed them, desperately at times, although I never owned up to it. I wanted to be part of my sister's family life, to see my parents again, to walk the streets of my youth, to show off my beautiful family. So when Robert mentioned visiting Brazil at the end of the one-year assignment, I jumped at the opportunity. Eric, age one, was still in diapers.

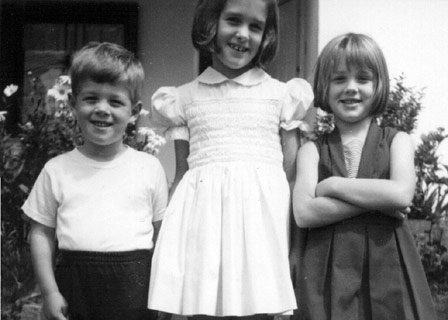

Eric, Laura, Carol, front steps of of Carrera Segunda Este house, Bogota, 1966 (photos by Elizabeth)

We rented the house to incoming faculty, much as the Merkls had rented to us in 1964. In the rush to get everybody ready for the international move and the house cleaned up and our personal belongings packed away, Eric almost got run over. He was hanging out with me in the girls' bedroom when Robert went out the door on a last-minute errand with the three older kids. I heard the engine fire up and looked around the room. Eric was gone. He had a habit of walking out to see the car leave, and I instantly knew what was happening. I must have reached the front door in three or four leaps, just to see Eric scrunched under the rear wheel of the Rambler. He looked so small and helpless, a tiny stunned silent bundle under the tire, his two legs a wedge under the wheel. My panicked scream came after the fact, because Robert had already stopped the car to see what was in the way. Eric had deep red dents in his legs from the blacktop but was otherwise unhurt. It was a sobering event. Leaving a sparkling house and writing detailed notes for the tenants took their rightful place in our priorities.

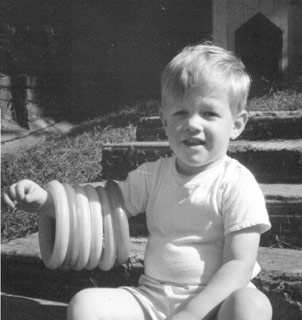

Eric and Mom, backyard of Carrera Segunda, 1966

It was a rather scruffy bunch that left California for Colombia, our clothing stuffed tightly in duffel bags bought at the Army surplus store. There was a good reason for the duffel bags, other than price; they held an unbelievable (rumpled) amount of clothing. We landed in Bogota in the wee hours of the morning. In true Colombian tradition, the $80 I had brought to spend on souvenirs was lifted from my carryon, either at the airport while waiting for passport control, or later in the taxi. The chatty driver helpfully loaded our baggage in the front seat next to him, while we all sat in the back. He wore a ruana, the traditional Indian blanket, so it would have been no problem for him to rifle through our bags on the drive to the hotel. We lodged a fruitless complaint, perhaps unfairly because my money could have been lifted at the airport, the usual place where Colombian pickpockets relieve Americans of their cash.

Elizabeth was a friendly face to greet us at the hotel. She had flown down a couple of days ahead of us. Not knowing the language, she could do little to find us housing. Universidad de los Andes soon connected us with a family subletting their fully furnished place in the tony section of Bogota, on Carrera Segunda Este. It would be our home for the next six months. The Education Abroad program helped out with the exorbitant rent, something like $950 per month. Elizabeth was taken aback by the grim Colombian population, small, dark, unsmiling people scurrying about wrapped in black shawls, hats and shabby suits. People would stop us in the street to admire our postcard children, especially Eric. Flattering as this was, we worried about the kids' safety. Colombia was at that time, perhaps still is, deeply divided by feuding political parties, and children of foreigners were highly prized by kidnappers. On the road to the coastal city of Cali, which we fortunately never drove, buses were known to be ambushed by gangs armed with machetes who would line up the passengers and ask them what party they belonged to, and chop off the heads of those who gave the wrong answer.

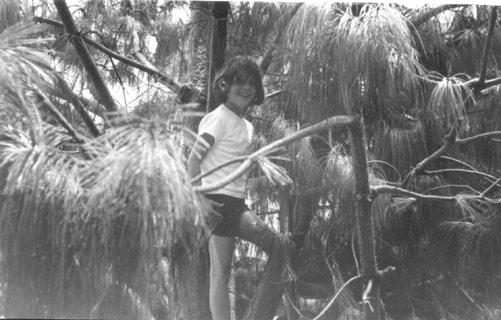

Laura, Richard, Deborah, backyard at Carrera Segunda

A joke making rounds among Bogotanos went as follows: when God created the world, he gave Colombia the greatest weather, the most beautiful landscape, the clearest sky and the greatest abundance of wildlife, forests, rivers and mountains. But, seeing as he was playing favorites, God bestowed on Colombia the very worst people on Earth. And so it was. The American community lived in suspicion and isolation. Down the hill from us, burglars regularly hit the American ambassador's car and triggered the alarm. It became our joke—must be two AM, there's the ambassador's car alarm. Toward the end of our ten months in Bogota an American acquaintance took me to visit the country club where the upper class enjoyed a life of privilege. This was another world, a peaceful, genteel island in that city of fear. It would have made a huge difference to belong.

We initially enrolled the children in the British school, run Nazi style by a dried-out spinster. Laura soon became terribly unhappy, Carol fell behind in arithmetic, and Richard developed deep circles under his eyes, so we relented and transferred them to the American school a block away. I think the reason for the British school was Robert's belief that British education was superior to American. Was he right? Who knows, but in any case things went better after we transferred them. Paranoia (or perhaps it was reasonable caution) dictated that the children should be accompanied by an adult and dropped off at the classroom door—not the school gate—even though we lived one block away.

The news that Carol was lagging in math marked the inception of home schooling, a family institution that would plague the children for the rest of their growing years. I sat down with Carol for some tutoring, but Robert soon took over. Mommyschool became Poppyschool and as much a fact of life as sun in the morning and stars at night. It would eventually fill every free moment of the children's day.

Eric at our second house, Carrera Primera Este, Bogota

Our

task in Bogota was to be in loco parentis to our 16 American

college students. I believe I was expected to be den mother, but I hardly

got to know them. Robert accompanied the group on local tours. I had to

stay behind, in any case, because the van they used for transportation

had room for no more than sixteen. My participation would have required

a second vehicle. I felt left out, especially when they drove to the edge

of the high Colombian plateau, where the terrain drops some 3,000 meters

to sea level, and where moist ocean air condenses into huge clouds to

create a sub-tropical rain forest. But I was glad to be out of the loop

when one of the students, a 19-year-old girl from Reseda, suffered a stroke.

She lay in a coma at the hospital for several days. After many efforts

to place an international phone call, Robert finally contacted her parents

via somebody's ham radio. She recovered, but that was the end of her junior

year abroad.

That was also the last year of that particular program, thanks to Robert's intervention. Ever the believer in book learning, he was appalled at the quality of instruction at the university, and deaf and blind to the educational value of a year in another culture. All he considered was academics, and Colombian education fell far short, no doubt. He sent so many damning reports home to UCSB that the program was terminated at the end of our stint.

We were quite isolated from the US, in those days before computers. Telephone calls had to be placed ahead of time, didn't always go through, or went through crackly and garbled. Air mail took a week or more to reach California . In a close call, we almost lost our property in Goleta . Robert had sent in several mortgage payments in one lump sum, not realizing that the bank still required their monthly check. To stop foreclosure took many phone calls and the intervention of the Education Abroad office in California..

Like most Americans, I hired a full-time maid, Atenaiz Perdomo, a good worker who loved the children. She was paid $2.50 a day. Robert called her worthless and was uneasy at her hugging the kids—if she loved our son so much, she might steal him. Atenaiz was visibly heartbroken when we left, especially for losing El Santo Padre, her nickname for Eric. I wrote to her after we left, but she never replied.

Passport photo, 1967

Bogota took its toll, and not only because of the 8,600' elevation or the crabby headmistress of the English School.

Elizabeth, who visited with us for three weeks, was sick most of the time and survived on my afternoon popcorn. I ran a low-grade fever for six weeks. The children acquired a menagerie of worms, despite my soaking lettuce in bleach water, washing fruit in hot soapy water, and boiling milk. We lived through a 6.5 earthquake that felt like a kicking donkey to us up on the hill, and wrecked the unreinforced brick houses on the flatlands below. Halfway through the year, our landlady bought a property a block further up, and we reluctantly packed up to move up to their beautiful house on Carrera Primera Este. But one fine day, like most good or bad dreams, the ten months in Bogota came to an end. Avianca whisked us from Bogota to San Juan de Puerto Rico, our first stop on the way to Brazil.