LAURA

I want to write, "she was born September 16, 1959, in Princeton, New Jersey," as if she sprouted then. . . but what I see is that Laura dated back to my marriage to Robert Wesson, May 31, l958, in Pôrto Alegre, Brazil. She began as a thought in our minds, sometime in the summer of 1958, in Cambridge , Massachusetts.

Robert and I were quite new at this business of really getting along with someone else—at least for myself, I can say that my previous two decades had been a time of waiting that did not entail a real commitment to another human being. But Fate intervened, and Robert showed up. He seemed quite right for me, unmistakably so. The stilted wedding ceremony officiated by my father had the heaviness of a funeral. Rather than gaining a son, Father felt he was losing a daughter, and he was right in that. I would not see my parents again until 1967, nearly ten years later.

We spent the first months of married life with his parents in their spacious apartment overlooking the Charles River. Robert had a summer to burn before starting work on his PhD at Columbia in the fall. With no house of our own yet, we would wind up in Princeton after a brief look at the shabby housing New York had to offer. In any case, Princeton had a good library for his research and fairly easy access by train to Columbia, not to mention fresh air and semi-rural living.

We wanted a child. I had assumed that I would become pregnant right away, but we had many months to wait. Elizabeth, my mother-in-law, attempted to comfort me with the statement that "some women are just not blessed with children, dear." As it turned out, it was wise of Laura to wait, because we spent weeks in a rented room, then in a dingy walk-up flat in New Brunswick, New Jersey, before we settled down in late fall l958 into our two-bedroom stucco house on Bear Brook Road and I became triumphantly pregnant.

Motherhood had many meanings—proof of my adequacy as Robert's wife, a handsome trophy to wave in front of his mother, and the natural longing for a child. However, much as I wanted a baby, I had grown up in a home that regarded children as the fate of ignorant Brazilians who don't know how to use birth control. Many a woman in our church had entered married life as a beautiful lass just to become a toothless hag right before our eyes as she popped out a baby a year. On the other hand, Robert had warned me before the wedding, in writing, that he wanted us to have twelve kids and that when they cried at night he planned to poke me with his elbow to tell me, "baby's crying, dear." I didn't know then that he was half serious. So my views of motherhood entailed many contradictions, most of them totally unconscious.

I

waited out the nine months hour by hour. I became a baby with a mother

wrapped around it. I already lived that child that was only beginning

to kick in my belly. I studied books and went to classes on natural childbirth,

sewed maternity clothes, and even tried to knit. Robert may have felt

left out, or not, but in reality he did not participate much in the changes

going on for me. He already had sired four children in Costa Rica from

a live-in relationship, and fatherhood was not a new experience to him.

Meanwhile, always ready to run myself down, I thought--they regard me

like a cow, watched at a distance for her milk output.

Married life brought an abrupt shift in our relationship. I gave up the constant arguments that had marred our engagement, the conflict between my longing for the glamour of movies and novels, and Robert's grim approach to life. I rather surprised myself with my resignation to a decidedly secondary role of Robert's satellite. Life shifted radically to purposeful deprivation, a life where Reason did not allow for Luxury. For instance, I owned one pair of shoes during my first winter in the States, finally buying a pair of sneakers when the shoes began to give me painful heel spurs. Meanwhile, Robert owned stocks valued in the six figures, money saved for a rainy day that never came.

As I gave up my demands for romance, life became a trial to be endured, pain-avoidance rather than pursuit of pleasure. I blamed Robert for my unhappiness and punished him with the only weapon I had, sullen, silent resentment. Perhaps he took refuge in his work, beginning with the writing of a PhD dissertation, one of the few goals on which we completely agreed. In May, a year married, we drove to Trenton for a picnic by the Delaware River. We drove back late and hungry. Our wedding anniversary found me shedding tears over potatoes in the kitchen, but it was no use to complain. Robert would have berated me as an ungrateful beast.

Laura emitted her first unearthly howl at 3:30 PM on September 16, 1959, ending a healthy pregnancy and uneventful birth aided by a couple of shots of Demerol. The delivery was strictly my business: Robert dropped me off at the hospital and retreated to read and take a nap at home. The doctor semed surprised when I refused his offer to call the father with the good news, but after all, Robert hadn't bothered to call the hospital either. He did not know his fifth child had been born until two hours after the fact.

Whether from the Demerol or the sheer physical stress of childbirth, I felt very confused and mortified that I forgot my married name. When the newborn was brought in for me to hold, I tried to play with her as I had done with my turtle and cats and dogs, but this was an unresponsive stranger. Expectant parents need to be warned that a newborn baby does not smile or look you in the eye, and only time and human contact shape him or her into a member of the family.

My return home as a mother came as a shock. I could never have predicted the wave of depression, sadness, resentment, the storm of feelings that the birth unleashed. I was now the older generation, second fiddle to a red brat. I became acutely aware of death as a presence right around me. I needed a vacation from all the expectations and hopes, trauma and letdown, but now I was on call twenty-four hours a day. I didn't dare tell anyone, especially not Robert, that I had changed my mind about being a parent, that I wanted to give Laura up for adoption or take her back to the hospital. Now must I share my meager allotment in life and look happy about it. In effect, I had mortgaged twenty years of my life to meet expectations that were not truly mine.

Fortunately, babies grow up. They begin to smile and play. One fine day, right on schedule around six weeks, Laura slept through the night. My painful bottom healed, my strength returned, and even my sex drive came back. It helped that strangers stopped me in the street to tell me she was the most beautiful child they'd ever seen. One evening after her daily bath (Robert remarked that a bath a day was a law of Nature for Laura), I sat her on the edge of the table and we laughed, eye to eye, laughter meeting laughter for no reason at all.

Laura came into the world with a heavy baggage of expectations. When she followed a flashlight with her eyes at three weeks of age, we knew she was an Einstein. “Too bad she is a girl,” I dutifully said. “Men have more use for brains.” When one of her first words was "hot," we marveled at her capacity for abstraction. We worried about her fears, of a venetian blind spread out on the floor, of a pingpong ball bouncing on the linoleum. Robert worried that she would be at serious risk for mental illness if she got jilted in love someday, because of her "fragile nervous constitution." I think he was talking about himself.

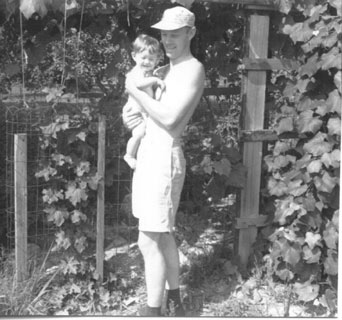

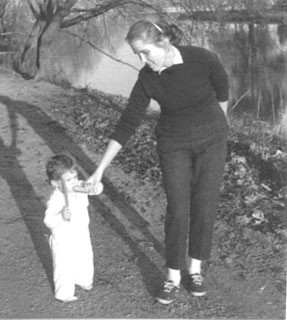

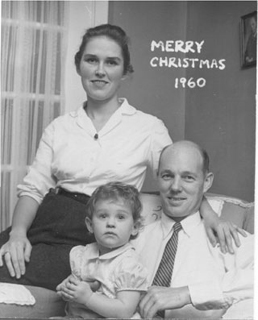

Elizabeth, Robert (with Laura), Laurence. Cambridge, MA1960

Indeed, Laura was what is usually called a "difficult child." She cried a lot and often refused to be comforted. Years later, when our fourth child woke us up every night for a solid year, we pragmatically experimented to see what worked to calm him down (the overture to Tannhäuser played at full volume worked better than a spoonful of whiskey, we found). With Laura, we talked and worried and chewed our nails. Our one attempt to leave her at the church nursery to attend the Unitarian service came to an ignominious end after she screamed for a solid hour. We were politely urged to leave her home next time. The paternal grandparents also offered their usual solution—we must take our cranky baby in for extensive medical testing. In Maine, when she was nearly two, the dean of Bates College invited us out to dinner. Leaving Laura with a babysitter was out of the question. I nibbled what I could with my daughter standing next to me on the chair, arms wrapped tightly around my neck like a boa constrictor.

As years passed, Laura obligingly measured up to our opinion of her as a genius. She learned calculus at age 9. A private tutor Robert hired to teach her quantum mechanics wrote us a three-page letter upon quitting the job: Laura didn't need more math and physics, she needed to be a child; she needed to have free time to be creative. I am afraid his words fell on deaf ears. Laura would leave for college at Cal Tech at age 16, would be hospitalized with a nervous breakdown at age 18, and would disappear from our lives after graduating from Tech in 1980.